MACHAIRA: The Carnage of Troy | Vases to Look at

MACHAIRA: The Carnage of Troy

Vases to Look at

Visual Narratives

In the Archaeological Museum of Cerveteri, there are two Attic ceramic masterpieces (end of 6th century – early 5th B.C), in display since 2014 in two different cabinets, in the middle of the hall, at the first floor. One is the Euphronios krater, known also as the Sarpedon krater, because of a scene on the side A, in which Sarpedon’s corpse is carried away from the battlefield. The second is a kylix made by Euphronios and painted by Onesimos, with scenes from the Ilioupersis, or the sack of Troy. During the second half of the last century, these two famous vases were illegally taken from Cerveteri and brought to USA, one to The MET of New York and the other one to the Getty Museum in Malibu. In 2014, after a long and difficult international letter rogatory, thanks to a team-work consisted of the Italian magistrates, the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and the Italian Police for the Safeguard of Cultural Heritage, these precious artifacts could finally come back. Testimonials of “rescued art”, these famous artworks of vase painting are extraordinary, especially for the images they carry on, made by some talented Athenian painters, in activity from the end of the tyranny to the Persian wars (510-480 B.C.).

It is no coincidence that the most remarkable samples of this technique were found in Etruria. Among the different themes painted, the war tales of Troy have a special place, due to the fortune of the narrative plot and to the drama of the represented scenes. In the exhibition of Franco Minissi, the lantern-shape and the closet-shape elegant showcases, under the hall’s arch, make these masterpieces dialogue with other pieces through many elements in common. An example of these relationships is the Hydria Vivenzio (named “Vivenzio” after the first owner’s name), found at the end of the eighteenth century in Nola, in the Naples district, and hosted in the lantern-shape display, closest to our two masterpieces. This jewel of Magna Graecia, lended by the Archaeological Museum of Naples for the occasion, was indeed painted with scenes from the war of Troy.

As evocative title of the exhibition, the Greek word Macaira was selected, name of a typical knife used in ritual sacrifices to cut the enemy’s throat, as displayed on the kylix of Cerveteri and the hydria of Nola.

The Machaira

Curved-bladed sword known as Machaira

This is not an ordinary knife but a big sword like a scimitar, with a single cut curved blade, getting larger toward the extremity. Differently from other blades used in ancient times in close contact fighting, in Greece the machaira was the greatest instrument for cruel sacrifices and therefore, commonly in ritual killings. The scenes on the kylix of Euphronios and on the Vivenzio hydria, together with several other examples, demonstrate that this knife, capable of horrible mutilations, in iconography was used where – in addition to the usual division between good and evil characters – there was a victim who had to die for a coup de grace of an executioner. Therefore, differently from an ordinary war scene, such as duels are, actually, killing scenes with a machaira are ritual sacrifices with an intended victim. Such peculiar blade has also a symbolic meaning, always related to the shedding of blood and sometime to the idea of revenge: by the remaining pictures, Apollo uses it to kill Tizio and Achilles holds it, when Priam meets him in his tent, to plea for his son Hector’s corpse.

Greek myths and Etruscan aristocracy

Due to several ramified connections between main Mediterranean communities, not only exotic artifacts arrived to the Etruscan coastal cities but people, carrying different ideas and lifestyles. In particular, Greek myths with their tales of deities and heroes sounded fascinating to the Etruscans, because they represented more than a religious world but, overall, novels to tell, behaviour patterns, ethical models and political messages. Since 7th century B.C., Greek myths are painted by the artisans of Caere, the sign of an Etruscan customers’ early interest for Greek mythology and all its meanings.

In 6th and 5th century B.C., to the southern port cities of Etruria, many vases made in Athens arrive, on demand of the local aristocracy. Therefore, Athens becomes an artistic pole, strongly connected with the Etruscan market. Such massive request of this kind of artifacts and visual narratives from the Etruscan elites shows their capability to recognize such language by pictures and to share the complexity of their codes and meaningful relationships. The objects and scenes chosen for banquets, grave goods or sanctuaries show how Etruscan aristocracy wasn’t a passive and an unaware user of such rich iconographic assets but, on the contrary, it owns an independent capability to reprocess meanings and symbols, according to its needs.

The backgrounds

Aerial view of the excavation of the sacred area at Sant’Antonio in Cerveteri

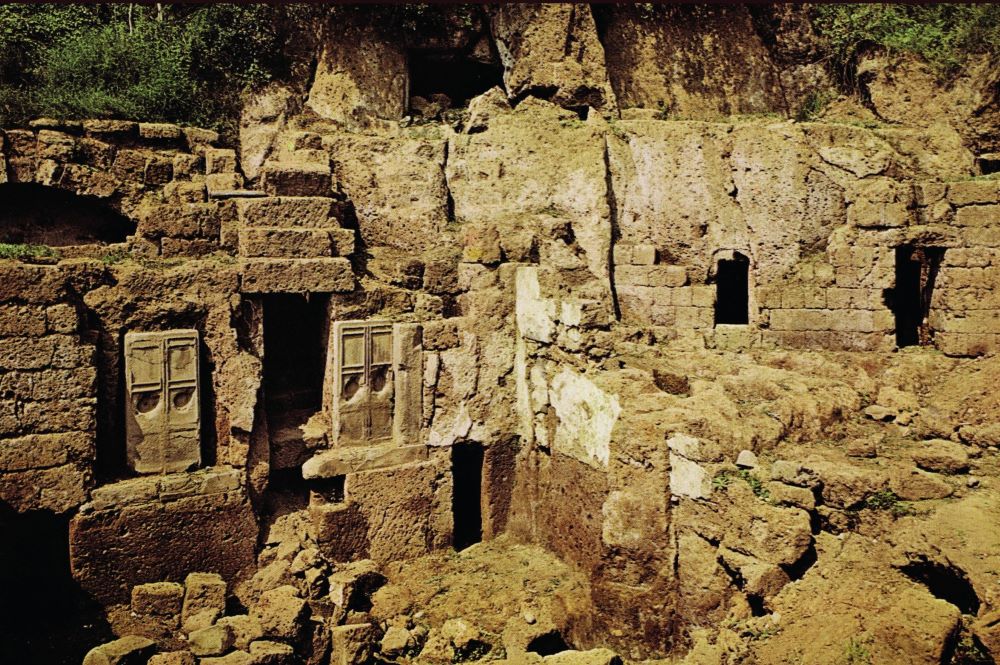

Rock Necropolis in the locality of Greppe Sant’Angelo in Cerveteri

Caere

Although they have been stolen, we know the backgrounds of our masterpieces. The krater is from the Greppe Sant’Angelo necropolis, in the southern area of the city upland, next to the ancient way to Fosso della Mola valley, famous for its statues of Charun and some lions (4th century B.C.). The discovery of the krater shows that Greppe necropolis was already used at the end of 6th century B.C.

Over the necropolis, near the same ancient road to the city, there is the Sant’Antonio sacred area. There are two sacred buildings, one dedicated to Hercules and the other to Rath, the Etruscan Apollo, in his role of prophetic and purificatory divinity, and then an altar for Turms, the Etruscan Hermes. The monumental kylix comes from that area.

Nola

The hydria was found in 1797 in Nola, an important city of eastern Campania, in the eastern area of Neapolis, controlling a very fertile land, already famous in ancient times for cereals production, owned by the local landed aristocracy.

The artifact had been placed inside a pithos (a vase for food) as cinerary urn, in order to host ashes together with five alabastra, containers for ointments and perfumes. Inside the pithos were found other grave goods with some ashes remaining. There are some strigils, related to the gymnastic aristocratic activity, knives, brooches, fragments of a bronze vase, mother-of-pearl and modelled bone fragments. Furthermore, mixed with ashes there are cereals and legumes related to the agricultural production.

The refinement of burial goods and the prestigious ritual of incineration are signs of a burial of great importance.

Testimonials of rescued art

The rescue of these Euphronios Attic masterpieces represents one of the best results of a great investigative and diplomatic job, leaded by the Italian police for Cultural Heritage Safeguard and the Italian Public Prosecutors. In particular, the magistrate Paolo Ferri had a fundamental role as responsible of the investigation on the market of stolen art, at the beginning of Nineties of last century, the biggest illegal market after drug and gun trafficking. He rescued the precious artifacts, but also more than thousands other pieces, illegally taken, recorded and kept in Switzerland by merchants of stolen art. The krater was taken from the necropolis of Greppe Sant’Angelo and sold to The MET of New York, for the huge amount of one million dollars, at the beginning of Seventies, while the kylix was stolen in the sacred area of Sant’Antonio and illegally sold, in fragments, between 1983 and 1985, to the J. P. Getty of Malibu.

A dedication written in typical Caere’s alphabet fonts and other matching fragments found in the sacred area were proofs for this place to be its background, beyond any reasonable doubts.

The vase was given by the Getty Museum back in 1999, because of the uproar caused by the investigation, while the krater was given back only in 2006, through diplomatic agreements between Italian and American governments.

Ancient vases and modern controversy

Because of the peculiar circumstances in which they were found and sold abroad, the artifacts became the bone of contention, since their discover, on which journalists, insiders and pundits have been confronting on. After the evidence that these vases came from Italy, in particular from the Etruscan city of Cerveteri, where other examples of the famous workshop of Euphronios were been found, main topics of conversations have been: what is the value of these precious artifacts made by the creative Greek genius, if they have been taken away from their background? Do their historical and cultural values decrease or does their inner historical-artistic value prevail? Some American historians of ancient art have maintained with specious arguments that the value of these masterpieces goes beyond their backgrounds. On the contrary, archaeologists more careful about the contexts, think with detailed reasons that the backgrounds are fundamental to read the artifacts and their many historical meanings. The facts show that, in presence of intercultural phenomena, background data are essential to understand artworks and high level craftmanship, conceived and made in a specific cultural environment but received by another, completely different from the original, although capable to understand meanings and ideas of their makers.